Of late in my conversations with fellow development professionals I have begun to realize that we are becoming more and more “comfortable” in the slowness of the social change process and I would go on a limb to say that we are guilty of slowing it down further. It almost makes essentialist, that the positive change for whose agents we claim to be is slow because those who are the beneficiaries of this change are hard to convince. While simultaneously the same colleagues are eager to adopt new social media tools for bringing about social change. So why this contradiction. At one end the slowness of social change is being taken as a given but at the same time this euphoria around social media as a way to leapfrogging social change? Grasping at the straws are we?

Perhaps the answer is somewhere in the way we are going about the business of international development. Traditional approaches to international development place greater emphasis on planning and strategy development relying heavily on ex-ante analysis, projecting an image of certainty and control through detailed fore-planning which often places penalties on deviations from plans during implementation. This approach though tries to break away from “one size fits all (OSFA)” by being consultative in its design at the on-set but repeats the draw backs of OSFA approach by assuming that on going lessons from implementation are irrelevant to planning. So now we have a situation where the plans no matter how well planned from the outset are being followed rigidly and monitoring is done only to ensure that they do not diverge and compliance with planned activities or outputs is controlled. As an international development worker this would offer little opportunity to be creative or flexible in responding to information emerging from implementation. Which is where the euphoria for new tools such as social media provides a release for jaded development workers. It provides this appearance of being able to change course, appear to move quickly in face of new information. This in my opinion creates an illusion that ‘improvements’ to plans can be executed in a way that lead to positive change in “real time” which traditional development approach cannot.

The idea of social media has seemed to promise answers which are attractive both to who espouse the traditional approaches and to those looking for non-traditional ways of social change – because social media is associated with those committed to ideas about participation and grassroots empowerment. Since a lot of the people who are adopting social change may or maynot be directly connected in their day to day functioning with the grassroots they think because social media connects them to a certain kind of grassroots, that seems to be solving the connection issue. But this impatience in my opinion does more harm than good, it is IMHO what sensational journalism is doing to investigative journalism.

Impatience for seeing change happen is important but it should not be overtaken by illusion of change. It provides international development actors ways to network, find supporters, fundraise, inform and lobby online. But real meaningful change in lives of individuals, poverty alleviation, improve program implementation – it does not. As long as that is clear we can justify the % of resources we spend on it.

Update 25 July 2013:

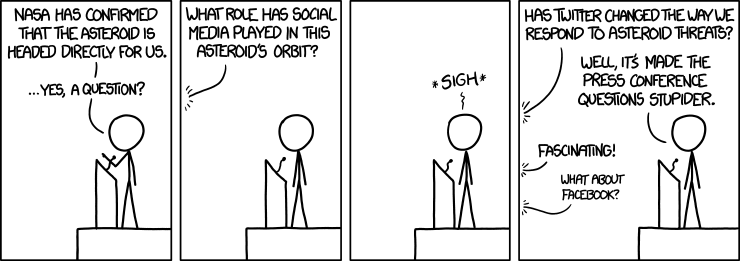

When I saw this in xkcd I had to add it here! It makes sense here. I do not like how every programme implementation conversation ends up having someone always ask but what about how we use facebook, or twitter.

From: XKCD.com For more go to http://xkcd.com/1239/